St. Josemaria and Franco's last victims search for solace

John Paul II and his Mystical Bride St. Josemaria Escriva see the John Paul II Millstone http://jp2m.blogspot.com/2007_06_01_archive.html were cohorts of General Franco of Spain. The Opus Dei produced, directed and controlled the 26 years papacy of John Paul II and brushed under the Vatican carpet the victims of the John Paul II Pedophile Priests Army. St. Josemaria Escriva was obssessed with his own political and church titles he'd sleep with the Devil's brothers Franco and Pinochet see the John Paul II Millstone for details http://jp2m.blogspot.com/. It is no surprise that the priests during Franco's dictatorial regime also were pedophiles as it is now being revealed for the first time.

St Josemaria Escriva cared only for his own flock and ignored the victims of Franco and Picochet and so it is not a surprise that the Opus Dei also ignored the tens of thousands of the John Paul II Pedophile Priests Army http://jp2army.blogspot.com/ in the USA and worldwide!

St. Josemaria Escriva hated the Jesuits their Liberation Theology that fights against the likes of Pinochet and Franco and so the Opus Dei are now suppressing them by closing down the Vatican Observatory and expelling the Jesuits from the Vatican Radio and most of all silencing the Jesuits who work with the poorest of Christ Jon Sobrino see the Benedict XVI-Ratzinger God's Rottweiler for details http://pope-ratz.blogspot.com/

Letter from Escriva to Franco

http://www.odan.org/escriva_to_franco.htm

In the following letter, Opus Dei founder, Escriva, congratulates Spanish dictator Francisco Franco on the union of church and state in Spain. According to Giles Tremlett [1], "Opus Dei's 84,000 members around the world deny [Escriva] actively supported Franco;" however, this document shows that at the very least Escriva admired Franco.

Opus Dei also denies that the organization has a political agenda, and claims that its members have complete freedom as well as personal responsibility for their actions. However, the following quote from Escriva's book The Way, which Alberto Moncada [2] describes as a summary of Escriva's "national catholicism," illustrates how difficult it would be for a member of Opus Dei to reconcile this personal freedom with his counsel:

"Nonsectarianism. Neutrality. Those old myths that always try to seem new. Have you ever bothered to think how absurd it is to leave one's catholicism aside on entering a university, or a professional association, or a scholarly meeting, or Congress, as if you were checking your hat at the door?"[3]

Letter from Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer

to Francisco Franco, May 23, 1958

The following letter, translated from Spanish (original Spanish text found here) was published in the January-February, 2001 issue of Razón Española (magazine title means Spanish Reason). Copies of this and other letters from Msgr. Escrivá de Balaguer to Franco are kept in the Fundación Nacional Francisco Franco (National Foundation of Francisco Franco) (Marqués de Urquijo, 28, 28008 Madrid, Spain). The originals belong to Generalísimo Franco’s only daughter, Carmen.

To his Excellency Francisco Franco Bahamonde, Head of State of Spain

Your Excellency:

I wish to add my sincerest personal congratulation to the many you have received on the occasion of the promulgation of the Fundamental Principles.

My forced absence from our homeland in service of God and souls, far from weakening my love for Spain, has, if it were possible, increased it. From the perspective of the eternal city of Rome, I have been able to see better than ever the beauty of that especially beloved daughter of the church which is my homeland, which the Lord has so often used as an instrument for the defense and propagation of the holy, Catholic faith in the world.

Although alien to any political activity, I cannot help but rejoice as a priest and Spaniard that the Chief of State’s authoritative voice should proclaim that, “The Spanish nation considers it a badge of honor to accept the law of God according to the one and true doctrine of the Holy Catholic Church, inseparable faith of the national conscience which will inspire its legislation.” It is in fidelity to our people’s Catholic tradition that the best guarantee of success in acts of government, the certainty of a just and lasting peace within the national community, as well as the divine blessing for those holding positions of authority, will always be found.

I ask God our Lord to bestow upon your Excellency with every sort felicity and impart abundant grace to carry out the grave mission entrusted to you.

Please accept, Excellency, the expression of my deepest personal esteem and be assured of my prayers for all your family.

Most devotedly yours in the Lord,

Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer

Rome, May 23, 1958

Franco's last victims search for solace

Uxenu Ablana, now 80, was taken from his parents in 1936, during the Spanish Civil War, by the Franco regime

Uxenu Ablana grasps the rails of the rundown house that once was like a prison to him. He breaks into an irreverent version of Cara al Sol (Facing the Sun), one of the songs drummed into him as a child when he lived at this former orphanage. It is a bitter-sweet moment. This was the marching song of General Franco’s dictatorship.

For Ablana, the song symbolises a youth lost to the dictator’s regime. “My life stopped in 1936,” he says. “They robbed me of my childhood.”

Now 80, Ablana is one of an estimated 30,000 “stolen children” of Franco’s Spain.

These sons or daughters of Republicans were taken from their parents during and after the Spanish Civil War in a sinister programme under direct control of El Caudillo.

Many were too young to remember who their real parents were. Others were lured back from exile under the pretence that they’d be reunited with their families, only to be sent to live with adults sympathetic to the regime. The children’s identities were changed so that they could not be traced.

Emilia Giron was persecuted by the Nationalist Government as it searched for her brother-in-law, a guerrilla. One of her sons, Jesús, was taken from her in jail, shortly after he was baptised, in the early 1940s. For 67 years, she searched fruitlessly for Jesús. In an interview with Spanish documentary-makers before her death last year, she said: “I know I gave birth to him. They took him to be baptised but they never brought him back. I never saw him again.”

This campaign of indoctrination was the brainchild of Antonio Vallejo-Nágera, the head military psychiatrist. Vallejo-Nágera believed Marxism was a mental illness that needed to be eradicated from Spain. A prominent psychiatrist in the 1930s, the manual of his theories, The Eugenics of Hispanicity, sealed the fate of a generation of innocents, such as Ablana.

Today those innocents are pensioners, many still desperately searching for parents, brothers, sisters — and their own identities — before it is too late.

When Ablana returns to the orphanages where he spent his youth in Pravia, northern Spain, painful and vivid memories flood back. His mother was tortured to death by Franco supporters to gain information about his father, who was sentenced to death, reprieved, then jailed. His crime: lending a car to officials from the Republican Government.

Ablana was thrown into orphanages from the age of 5. He spent 13 years being abused by priests and indoctrinated with propaganda from the Falange, the right-wing party allied to the Franco regime. The aim was to transform him from the son of a “red” into a follower of the regime. “The priests would beat you if you wrote or ate with your left hand. They thought it was a sign of being a red,” he says.

Ablana was denied toys and made to clean shoes while the orphaned children of Franco supporters played outside. Then there was the abuse. “One priest told me to take my trousers off, he said he was going to clean my feet as Christ did. But his hands carried on up,” he recalls.

He escaped from an orphanage at the age of 18 and was found by his father. But after years apart, the two were distanced and soon lost touch. He became a travelling salesman, married and has children. But today he is still marked by what he suffered more than 70 years ago.

Antonia Radas, another victim, finally got to know her mother, albeit briefly. The two had been separated when her mother Carmen was forced to give her up after being jailed for her husband’s Republican links. Radas lived a comfortable life surrounded by lies; her adoptive parents told her that her real parents had abandoned her. Her name — Pasionaria Herrera Cano — after the communist civil war leader — was changed to stop her from being traced. “My new parents kept telling me that my real parents were undesirables and had sold me. It was poisonous,” she says. Mother and daughter were reunited through a TV show in 1993. Radas shared 18 months with her mother before she died.

Now a frail 75, Radas, from Málaga, has mixed feelings about the reunion with her. “We had time to get to know each other. But it has been difficult to deal with what happened to me,” she says. “My mother was destroyed by the pain caused by not being able to be with me. She lived for 60 years with my photo under her pillow.”

Others, desperate to find loved ones, embarked on searches, using DNA tests to find their families. María José Huelga, 84, paid for tests on five women in France, Belgium and Spain, to find her sister, Maria Luisa. She is still looking.

After Franco’s death in 1975, much of Spain’s past was brushed under the carpet. The new democracy wanted to ensure the transition from dictatorship did not falter. An amnesty law ensured those guilty of crimes committed during the Franco’s reign couldn’t be brought before the courts.

As countries such as Argentina and Guatemala dealt publicly with the fate of those who disappeared during their dictatorships, Spain stayed quiet. It is only relatively recently that the fate of victims such as the stolen children has come to light. As the mood in Spain changed, campaigners asked questions about the generation of “disappeared”. People such as Emilio Silva, who at the start of the decade became the first person to search for the body of his grandfather, shot and buried during the civil war. He inspired others to embark on similar quests. Now barely a week goes by without a mass grave being reopened.

Paul Preston, the British historian who has written a book called The Spanish Holocaust, says: “We know the names of 101,000 people. But there are at least 30,000 mass graves across Spain.”

Despite changes, many believe Spain has a long way to go and early judicial efforts to give coherence to the campaign have hit the buffers. Two years ago, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the Spanish Prime Minister, introduced the Law of Historical Memory, which offered redress to victims or their relatives who were killed or “disappeared” during the Civil War and its aftermath. The law ordered the removal of symbols celebrating Franco. But the legislation failed to satisfy campaigners, who said it did not go far enough. For those on the Right, such as the opposition Popular Party, it served only to open past wounds.

Then, earlier this year, the Spanish judge, Baltasar Garzón, who rose to fame when he tried to arrest the Chilean dictator General Pinochet in 1998, launched an investigation into the fate of the “lost children”. But just as Spain seemed about to confront this dark chapter, Judge Garzón was forced to concede jurisdiction of the case to lower provincial courts. They are unlikely to pursue such a complex and controversial case.

Campaigners, however, refuse to give up. They are to take to court the case of Beatriz Soriano Rui. In 1964 she was taken from her mother while still in hospital and disappeared. Her sister, 44-year-old Mar Soriano Ruti, says: “I hope one day to set eyes on my sister.”

--

The lost children of Franco-era Spain

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/newsnight/8219250.stm

Watch the film in full

Sue Lloyd Roberts

BBC Newsnight, Spain

Seventy years after the end of the civil war in 1939 in which more than 350,000 people were killed, Spain is still divided over how to deal with what the country calls its "historical memory".

Many people, especially the older generation, say that it has been so long since the war took place that now it is time to forget.

General Franco

General Franco ruled Spain as dictator for 36 years

However, those related to victims of the Franco era, and the younger generation, say that it is necessary to know about the events of that time, that they owe it to those who died.

Old battle lines are being redrawn.

When Franco died in 1975, there was an agreement between his friends and foes, often dubbed the "pact of forgetting", in which both sides agreed a mutually beneficial amnesty to paper over their divisions in order to move forward to a modern, democratic Spain.

Unlike South Africa, Spain has never had a truth and reconciliation commission, so only now are long-repressed aspects of Spain's dark past coming to light.

Young volunteers

The dead on the losing side of the war had been thrown into unmarked, mass graves, but people have not forgotten where they are.

the priest who, when we were sitting at the table, either eating or writing, had a cane and he would whip us on the neck if we used our left hand

Uxenu Ablana

In pictures: Spain's dark past

Exhumations are now taking place all over Spain. In Malaga, just metres away from Spain's famous Costa del Sol, teams of young volunteers work alongside academics and forensic scientists.

They are watched by old men who, as children, remember seeing their fathers rounded up by the Fascist troops.

"My father was assassinated," says 72-year-old Antonio Perez Ruiz. "Not killed because he deserved it. He was killed by those who in those days went around calling themselves nationalists. But who were these people? Do 'nationalists' go around killing fellow Spaniards, supporters of a democratically elected government?"

'Important work'

The young volunteers, working in t-shirts under the hot August sun, are as indignant as the old men.

Nuria complains that she was not told the truth about the civil war at school and she now wants to know:

"It's a bit late, but better late than never," she says. "The work we are doing here is important. We mustn't forget these people."

Woman working on grave exhumations in Spain

Exhumations are now taking place all over the country

As students and academics alike dig away at Spain's past, other horrific stories about the Franco era are emerging.

As people begin to talk about this period, we are finding out that some 30,000 children were forcibly removed from their parents, given to childless pro-Franco couples or put into institutions where they were brainwashed and cruelly abused.

We met Uxenu Ablana in Pravia, in northern Spain. He says his life came to an end in 1936 when, at five years old, he was taken from his parents.

His father had been a government driver and was imprisoned. His mother died and Uxenu spent 12 years in four different orphanages run by the Church and by the dictatorship.

'Armed priest'

Uxenu took us back to the first orphanage where he was called "son of a red" by the priests, whom he says had a fanatical hatred of anything left wing.

We all agreed to forget these things when Franco died.

Milagros residents

He told us about "the priest who, when we were sitting at the table, either eating or writing, had a cane and he would whip us on the neck if we used our left hand".

"On two occasions as he leant over, a gun fell out of his robes and fell to the floor and we realised that he had a weapon he could kill with," he said.

He was interned with his three brothers, all of whom died of tuberculosis.

The priest in charge, he says, used to abuse them sexually:

"The priests collaborated completely with the Falangists who had overthrown the government. They were paedophiles and they converted me to atheism - they were bad and I refused to believe a word they said."

'Nonsense' claims

In another orphanage, run by the Auxilio Social, the main welfare institution in Franco's Spain, Uxenu and the other children were made to sing Falangist hymns celebrating the godliness of Franco's followers.

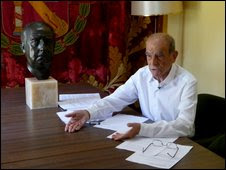

Dr Felix Morales

Dr Felix Morales says people like Uxenu are lying

Uxenu says that at the Auxilio Social orphanage he would endure serious punishments and go for up to 15 days without a meal at night.

"I complained, I cried, but there was no-one who cared. I never received any affection," he says.

Dr Felix Morales, vice-president of the Franco Foundation says people like Uxenu are lying:

"These people can say what they like, but it is not true. I don't know anything about these stories about what the priests and nuns did or any such nonsense.

"As all the people you spoke to well know, there was a department set up - the Auxilio Social - to look after poor children and war orphans."

Reluctance to talk

He goes on to claim that he had testimonies from children looked after by the Auxilio Social who went on to do well in life. And he claims that Franco's effect on Spain was positive:

Republican prisoners at gunpoint

Many still find the events of 70 years ago too inflammatory to discuss

"In 1936, when the war began, Spain was a poor country. I am old and I remember. It was a backward country. Franco left a different country - the eighth most industrialised in the world with a proud middle class."

Another exhumation is taking place in Milagros, in central Spain in an area which was pro-Franco during the conflict.

It is said to be still sympathetic to the dictator, so I am not surprised when my attempt to talk to local people about the digging down the road, was met with reluctance:

"We all agreed to forget these things when Franco died," they remind me. "It's been too many years," says one woman.

Only one local, born well after the war, was prepared to go further:

"I'll get the butcher to talk to you," he said. "He knows everything in the village".

But, after a few minutes, he came out explaining that the butcher would not talk because the subject was "incandente" that is, more than 70 years after the war, it is still an inflammatory subject.

You can watch Sue Lloyd Roberts' film on Franco's missing children on Newsnight on Tuesday 25th August 2009 at 10.30pm on BBC Two.

Listeners to BBC Radio 4 will also be able to hear a report on the PM programme at 5.00pm. Viewers of BBC World can also see her documentary Spain's Dark Past in the Our World series from Wednesday 26th August 2009.